Boulevard focuses on news about some of Louisville’s biggest employers, nonprofits, and cultural institutions. This is one in an occasional series about them.

Louisville’s economy was sizzling in 1951, when General Electric’s nearly 50-year-old home appliances business started construction on what would become one of the city’s single-biggest factory complexes. Louisville’s population had soared 15% in the previous decade, to 369,000, after World War II’s end shifted the U.S. economy back to peacetime prosperity.

GE appliances traces its history to 1905. But through its corporate parent and original driving inventor, it really extends even further back, to 1866. That’s when 18-year-old Thomas Edison moved to Louisville to work for Western Union. He spent most of his spare time tinkering, eventually losing his job. Many career moves later, he’d amassed a stack of patents for electrical inventions. The financier J.P. Morgan and a partner cobbled them into a company that formed the basis of General Electric.

That was the goliath that in the late 1940s and ’50s raced to meet post-baby boom consumer demand for toasters, mixers and “white goods” with the latest features — like the two-in-one freezer-fridges advertised in the 1952 TV commercial, top of this page.

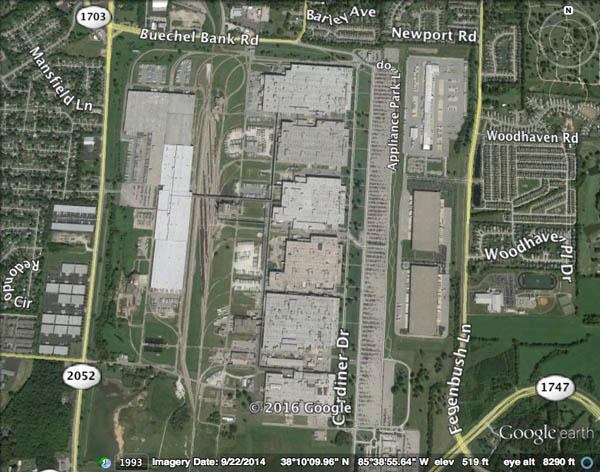

Appliance Park would eventually cover 1,000 acres in the county’s south end, with more than a dozen manufacturing, warehousing and power-generation buildings.

With Ford, International Harvester and other big manufacturers, GE launched a solid middle class with good wages and benefits that became the foundation of Louisville’s economy. At one time, the park employed 25,000 workers. It was a self-sufficient city providing many of its own needs, right down to mail handling.

Those good times started to ebb in the 1970s, as manufacturers sought cheaper labor by moving production overseas. Appliance Park now employs only 6,000 workers. GE put the home appliances division up for sale seven years ago, with Electrolux and the Asian appliance makers Samsung and LG taking part in talks. But they fell apart amid the financial crisis.

Then in September 2014, GE and Sweden’s Electrolux struck a $3.3 billion deal, only to call it off a year later when the Justice Department sued to block the sale, saying it would lead to less competition and higher prices.

Finally, in January 2016, GE and China’s Haier Group reached a far richer deal $5.4 billion — later increased to $5.6 billion — that passed Justice Department review, because the Chinese company had little U.S. presence, reducing the chances competition would be depressed. The sale closed June 6. Including other work sites, the division has 12,000 employees.

Finally, in January 2016, GE and China’s Haier Group reached a far richer deal $5.4 billion — later increased to $5.6 billion — that passed Justice Department review, because the Chinese company had little U.S. presence, reducing the chances competition would be depressed. The sale closed June 6. Including other work sites, the division has 12,000 employees.

Here’s an aerial photo of Appliance Park as it looks today:

Service work now in the lead

Jobs in health care, restaurants and hotels have become the fastest-growing part of Louisville’s economy. But they’re often part-time and don’t pay as well as factory work once did.

Factory employment last peaked in the Louisville metro area in 1999, when there were an average 95,000 jobs that year, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It then fell to a low of 60,900 in 2010, when the economy was still recovering from the Great Recession. The better news is that it’s crept up every year since, to 76,500 last year. But it’s extremely unlikely it will ever return to the glory days of 1951, when Appliance Park was king.